Wednesday 12 March

My first tattoo

The time had come, a day later than planned, to get tattoos. After a breakfast of ham and cheese croissants I headed out with Reece, Iz, Tilman and Ryan to the artist’s house in a leafy suburb of Harare. Several of Reece’s friends had recommended Kazz and we hoped that there would be time for each of us to get a small, simple piece as a permanent souvenir.

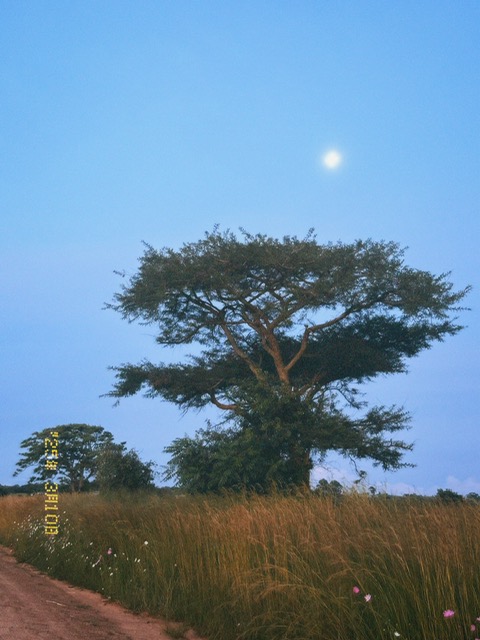

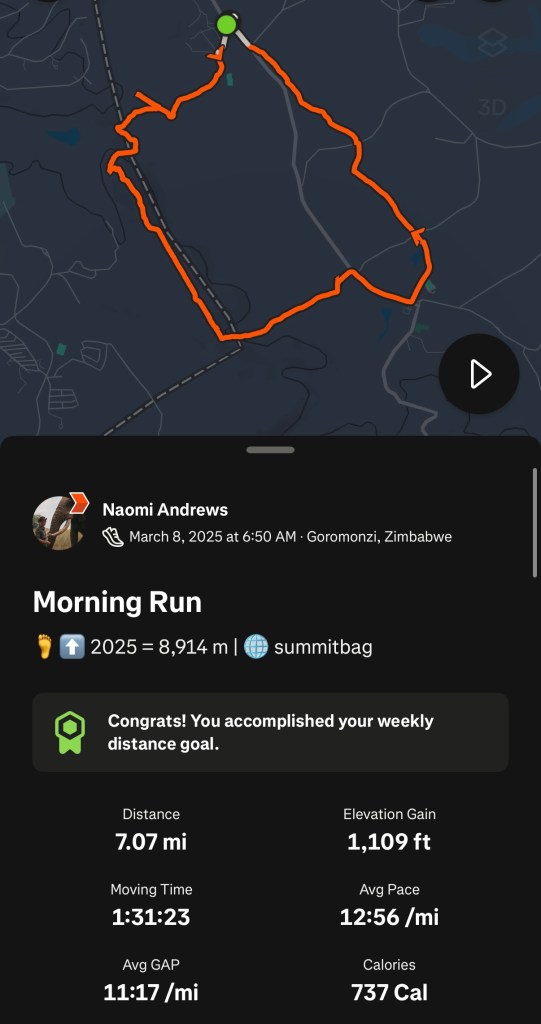

Kazz was tattooed, tousle-haired and very attentive. We talked through ideas and she came up with designs on an iPad while we hung around in her garden, eyeing the exotic-looking plants and huge boulders perched above a swampy green pool (she’d just moved in). She called us back into the studio room and tattooed four of us in turn while the others watched: Iz chose an acacia tree on her forearm, I had Mac the Imire elephant on my ankle, Tilman had an outline of Africa above his elbow and Reece had Nyami Nyami, the Zambezi river god, on his forearm. There wasn’t time for Ryan, but he didn’t mind.

The process took about 3 1/2 hours and I was blown away by Kazz’s artwork. First I showed her my idea, a line drawing of the elephant’s face, which she used to trace over a photo that Iz had taken at Imire. We discussed the size and location, then she printed and cut out a stencil so I could test it. I decided against having it on my foot as planned as she advised that it’d fade quite quickly, so I settled on my outer ankle/calf and lay face-down on the bench, watching birds through the window. It hurt a little, but wasn’t unbearable – just a scratchy feeling, which dulled as I got used to it, and took about half an hour. I was delighted with the result, as were the others, and we left clingfilmed and very happy – I thought my first tattoo well worth $60.

Our joy didn’t last long. It was 2:45pm and we were booked onto a wildlife sanctuary tour on the edge of Harare at 3:30, but we couldn’t leave Kazz’s house in the car as her partner had taken the electric gate fob. She was very apologetic as we climbed over the high garden wall onto the street. After a frantic phone call to Shelley, she and Bryn arranged to come and pick us up with Gus and Dan in tow.

Wild is Life

We traipsed along the road in the afternoon heat and were collected after a short walk. The drivers raced across Harare and we arrived at Wild is Life just a couple of minutes late. It was a much fancier setup than I’d expected, and I wondered if Shelley and Bryn had downplayed it so we had a nice surprise. If so, it worked: a path bordered by flowers and succulents led us to an open lawn dotted with trees, thatched buildings and – unexpectedly – an enormous , roaming kudu, which I gave a wide berth. It felt posh, a bit like Imire lodge. By the end of our tour, I understood why tickets cost $100pp.

Herbivores: elephants, giraffes, wildebeest & deer

We crossed the lawn and joined a group gathered by a baby elephant, Nina, who was nuzzling her human carer like a needy child. She was captivating. Our guide (Sean) explained how the animals are all orphaned or rescued, and as he spoke I looked beyond Nina to a wide, grassy plain, where giraffes, kudu, wildebeest, deer and a few small elephants roamed and grazed harmoniously. It was a wonderful scene and seemed quite surreal, having just come from the busy streets of Zimbabwe’s capital city.

Nina was taken away, trailing behind her carer as she held his hand with her trunk, and we were led up to a raised platform and handed leafy sticks. The giraffes knew the drill and strolled over with their easy, rolling gait. They used their teeth, dextrous lips and long, black tongues to strip the leaves as we held them up, and I was amazed at the strength in their skinny necks – we watched, amused, as a parent quickly retrieved a child dangling from a stick. It was amazing to stand so close to – literally underneath – such strange, elegant, nonchalant creatures.

We returned to the lawn and watched the elephants get led away in a line, jostling each other and being reprimanded when they attempted to upend some of the boundary logs that separated the visitor area from the plain. A small flock of runner ducks appeared from nowhere and wheeled past us, to our surprise, and we were ushered on to the next part of the tour.

Afternoon tea

Having not eaten since breakfast, we were delighted to hear it was time for afternoon tea. We walked over to a large, high-ceilinged, warehouse-like building, which we found to be filled with sofas, plants, rugs and random furniture that gave it an eclectic, shabby-chic and oddly stylish feel. Scattered tables were laden with teacups and tiered plates of cakes, sandwiches and scones, and we gladly established our place in a corner to settle down for an indulgent snack.

As we ate, a peacock strutted between the sofas, which seemed almost as bizarre as Gus sipping tea from a dainty little cup. We watched the herbivores through large, arched windows, then headed outside to see how close we could get. The grazing area came right up to the building and we leaned over a wooden fence to stroke Noodle, a friendly wildebeest, then climbed a spiral staircase to a balcony to feed handfuls of pellets to the giraffes; some took them more gently than others. Like at Imire, it struck me how several species of large mammal mingled together in one great, patchwork herd, content to share their space and utterly unfazed by their disparate neighbours.

Lions

After tea we were led behind the building to a wooded area. A deep purr betrayed the next part of the tour before we arrived at the enclosure. It was a thrilling, chilling sound that I felt as much as heard – a resonating, bass rumble that penetrated the air as if it were surrounding us. Two female lions – Savannah and Lucy – greeted us expectantly, purring and prowling along a high wire fence just a few feet away, lean muscles rippling through their sand-coloured coats as they observed us with a cool, black-rimmed, golden gaze. The guide threw them a couple of slabs of horse meat, which they plucked up before withdrawing into the trees. It was the closest I’d seen lions and I was struck by their size and composure – they were equal parts graceful and powerful, and they made me feel quite puny.

Pangolin

My disdain for the human race deepened during the next part of the tour. After a short walk from the lion enclosure, the group spread out along a large, semicircular bench in front of a man holding Marimba, aged 20, one of the world’s oldest known pangolins. Sean explained how this bizarre, armoured mammal is an elusive but highly sought-after target for poachers and traffickers, who profit from their meat and scales. These are made of the same keratin as our hair and nails but are believed in some cultures to have medicinal properties. Marimba is constantly accompanied during daylight hours by her carer, who cycles round with her in search of ants, and sleeps in a secret location unknown to almost all the staff. He might have the best job ever.

She was shown around the group at a distance, as pangolins are susceptible to human diseases, then released for a wander. She unballed herself and pottered along the ground on her two hind legs, leaning forward with her curved, blunt-clawed “hands” crossed in front of her, her long, heavy tail acting as a counter-weight. She was bigger than I’d expected, very cute, very slow, and – apart from her scales – heartbreakingly defenceless. We all fell in love with her immediately.

Hyenas

Next up, by way of contrast, were the spotted hyenas, which lurked in a wire enclosure just across from Marimba’s arena. Athena and Harry were each tearing into roughly hewn sections of meat, and we watched with grim fascination as their wide jaws – the most powerful in proportion to their size of any mammal – crunched effortlessly through bone and muscle. Harry rolled playfully around with his dinner while Athena dismembered a whole horse head, its toothed lower jaw dangling by a sinew.

Unlike the lions, I thought their beauty subjective: they looked like dogs that had been genetically modified, with huge, bear-like heads, close-set eyes, rounded ears, sloping backs and bow legs. Despite their appearance and their indiscriminate butchery, I found them oddly endearing – their tails wagged excitedly as they chomped and the guide explained that they’d been rescued as pups from a botched trafficking attempt at Harare airport.

More posh food

We made our way back to the big, central building, which was a relief as a throng of midges had descended on us as we watched the hyenas. We sat on a long table by an outdoor bar and made the most of that installation – I enjoyed a sparkling rose and discovered a love for baileys-like amarula in quite close succession. It was surreal to sit and relax so close to the herd of herbivores, which had been joined by a few ostriches, separated from us only by a boundary made of logs.

I wandered over to see an ostrich and was warned off getting too close by Sean, who explained that they’re powerful, spiteful animals that peck things for no good reason beyond being able to reach them. This was evidenced by a half-gouged tabletop, accessible to their beaks – which were slightly downturned at the corners, giving them a look of constant irritation – by virtue of long legs and necks. I eyed the bird warily and went off to stroke Noodle, who was much more accommodating.

Back at the table, a waitress came over with a large tray of canapes. The nine of us enjoyed filo pastries, smoked salmon, olives, cheesesticks, little quiches and other bite-sized snacks I couldn’t name, accompanied by a constant supply of drinks. We sat and talked under the trees as we watched the herd grazing contentedly, and I wondered if my life had peaked.

Evening

We left around 7pm, reluctantly, and headed back to the house in preparation for an early start to drive to Lake Kariba, where we’d be staying on a houseboat for the next few days. Once packed, we spent the evening checking our tattoos and discussing the merits of each animal at Wild is Life – and so ended another memorable day in Zimbabwe.